-

En una de las muestras de arte más concurridas en Europa de los últimos tiempos, el Musée de l’Orangerie de París acaba de hospedar, entre el 9-X-2013 y el 13-I-2014, la exposición ‘Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera – L’art en fusion’, dedicada a los dos más conocidos artistas plásticos mexicanos del siglo XX.

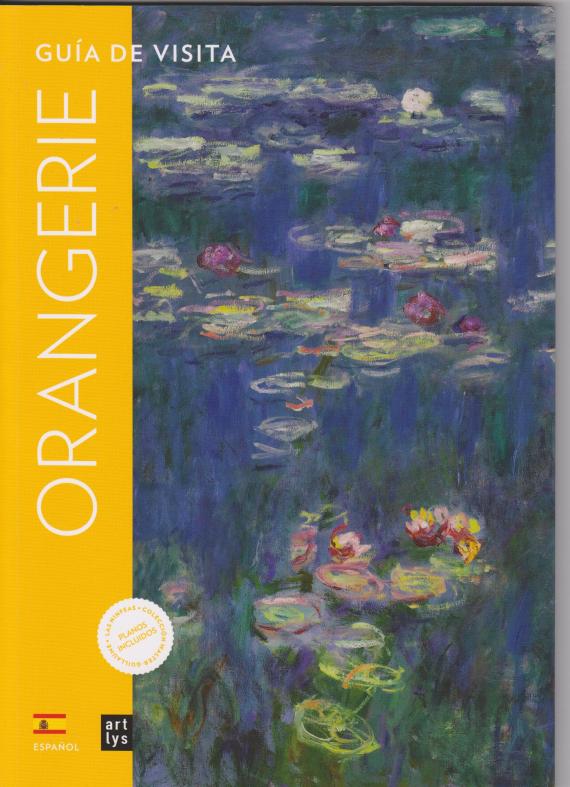

Esta muestra, que ya fue anunciada con antelación en esta bitácora (entrada del 28-IX-2013), ha granjeado un indudable éxito, generando filas interminables alrededor del museo (ubicado en el prestigioso Jardin des Tuileries, a la vista de la Torre Eiffel, y conocido sobre todo por albergar la célebre serie de ‘Los Nenúfares’ de Claude Monet).

Como es sabido, la relación entre Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) y Diego Rivera (1886-1957) no fue sólo artística sino personal: tuvieron una tempestuosa historia de amor, casándose en 1929, divorciándose en 1939 y volviendo a casarse el año siguiente. Si Diego correspondió a ‘las pautas tradicionales masculinas’ recurriendo a diversas relaciones extramatrimoniales, Frida también tuvo como amantes, entre otros, tanto a León Trotsky como a la cantante Chavela Vargas. Los dos vivieron un drama humano en el que también entró la precaria salud de Frida, doblemente víctima del polio como niña y, a los 18 años, de un accidente de circulación que la dejó media paralizada y sólo capaz de pintar desde la cama.

No obstante, es muy infrecuente que sus obras se exhiban juntas, y el gran desafío de esta muestra fue, precisamente, el de colocar la producción artística de los dos en un no siempre fácil diálogo. Pues la verdad es que, por muy cercanos que estuvieran en lo relacional, en lo que a su práctica pictórica se refiere Frida y Diego eran muy, muy diferentes. Si Diego se distinguió sobre todo por sus enormes murales (representados en la exposición por reproducciones) que adornan algunos de los más destacados edificios públicos mexicanos, y por sus temas políticos y sociales, la obra de Frida fue de cariz intimista, concentrada en el retrato y autorretrato, en las sensaciones de su cuerpo, y en la turbulencia emocional que tuvo su orígenes en la relación.

Se trató de una exposición cuidadosamente organizada, con la participación de responsables del Museo Dolores Olmedo de México DF, origen de buena parte de las obras expuestas. La opción elegida fue no mezclar indiscriminadamente obras de los dos artistas, sino alternar entre ellos en ‘bloques’ correspondiendo a salas o muros dedicados al uno o al otro. En un gesto ejemplar, los letreros explicativos aparecían en tres idiomas (francés, español e inglés), y las obras fueron complementadas por una amplia selección de material biográfico y fotográfico referente a los dos, y por una última sección que encaraba la ‘Fridamanía’ o el culto póstumo a Frida. Un muy generoso catálogo abarca las obras de la exposición y más, siendo enriquecido por artículos de especialistas.

En muchos aspectos, el contraste entre las obras ‘públicas’ de Rivera y las ‘privadas’ de Kahlo resulta tan extremo que, teniendo en cuenta también su no siempre pacífica vida íntima, uno podría privilegiar la noción de rivalidad y preguntarse si alguien sale ‘ganador’ de este encuentro entre titanes del arte. En dicho caso, sería quizás difícil no optar por Frida, y en este marco no deja de ser significativo el hecho de que es ella, y no Diego, quien protagoniza el cartel oficial de la muestra. En el catálogo también, es Frida la que luce en la portada, siendo el rostro de su marido destinado a la contraportada.

No cabe duda de que haya una fuerte componente de mexicanidad en la obra de las dos, desde los alcatraces que evoca Diego hasta la presencia en Frida de motivos referentes al atuendo tradicional mexicano. A la vez, es innegable cierta influencia europea en la sensibilidad de los dos: el padre de Frida fue alemán, y Diego por su lado pasó años formativos en Europa. No obstante, las obras, poco conocidas, de la primera fase de Diego acusan la fuerte influencia de géneros europeos, del fovismo al cubismo, y por muy mexicanos que sean los temas de sus murales, se puede vislumbrar cierta influencia ideológica del realismo socialista soviético. Si la originalidad es la calidad que más se busca en un artista, la preferencia debería inclinarse por la obra de Frida, con sus características de autointerrogación de la mujer, integración del mundo natural (la repetida presencia de animales como chango o perro), o la representación en sus lienzos de un tema hasta entonces tan insólito como la enfermedad.

A fin de cuentas, ¿se tratará, como afirma el título de la muestra, de una ‘fusión’ artística, o más bien de un perpetuo conflicto estético? Si el balance parece inclinarse por Frida, el fuerte talento de Diego tampoco es de negar. Podría ser lícito sacar de esta exposición un concepto de la relación entre hombre y mujer que, para su época, era más que profético y que anticipaba el terreno presente y futuro de la interactuación entre los géneros. Así sin duda será, en el siglo XXI en que no deja de crecer la icónica fama de la extraordinaria artista llamada Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo de Calderón – o, simplemente, Frida.

***

In one of the most popular of Europe’s recent art events, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris hosted, between 9 October 2013 and 13 January 2014, the exhibition ‘Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera – L’art en fusion’, dedicated to the two best-known Mexican plastic artists of the 20th century. This exhibition (earlier announced on this blog – see entry for 28 September 2013) proved a major success, giving rise to crowds snaking around the museum, located in the famous Jardin des Tuileries within view of the Eiffel Tower and best-known as home to Claude Monet’s celebrated ‘Les Nymphéas’ (‘The Waterlilies’).

As is well known, the relationship between Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) and Diego Rivera (1886-1957) was not just artistic but also personal: they lived out a tempestuous love story, marrying in 1929, divorcing in 1939 and remarrying a year later. If Diego fulfilled the ‘traditional male expectations’ with numerous extramarital affairs, Frida too had her lovers, including among others León Trotsky and the Mexican diva Chavela Vargas. Theirs was a human drama coloured by the precarious health of Frida, a victim twice over: of polio as a child and of a traffic accident at the age of 18 which left her semi-paralysed (she painted from her bed).

Nonetheless, it is rare to find the two artists’ work exhibited side by side, and the great challenge of this event was, precisely, to place their artistic production in a (problematic) dialogue. The fact is that, for all the closeness of their relationship, in their painterly practice Frida and Diego were very, very different. Diego is best known for his enormous murals (represented in the exhibition by reproductions), which adorn some of Mexico’s most important public buildings, and for his political and social themes; Frida’s work, by contrast, is intimate in nature, centred on the portrait and self-portrait, her bodily sensations and the emotional turmoil arising from the relationship.

The exhibition was meticulously organised, with the participation of representatives of the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City, which supplied many of the exhibits. The chosen option was not to mix up the two artists’ works indiscriminately, but, rather, to present them in separate ‘blocks’, dedicated to one or the other and occupying whole rooms or walls. In an exemplary gesture, the explicatory boards offered commentary in three languages (English, French and Spanish). The paintings were complemented by a full selection of biographical and photographic material relating to both, and by a final section devoted to ‘Fridamania’, or the posthumous cult of Frida. A comprehensive catalogue assembled the works from the exhibition and more, with articles by specialists.

In many aspects, the contrast between Rivera’s ‘public’ works and the ‘private’ art of Kahlo appears so extreme that, if one also recalls their rarely peaceful personal life, it might be tempting to prioritise the notion of rivalry and ask whether one or the other emerges the ‘victor’ from this meeting of titans of art. Should that be the case, it could prove difficult not to opt for Frida, and in this connection it is significant that she, not Diego, is the subject of the official exhibition poster: the catalogue, too, features Frida on the front and Diego only on the back.

There is, of course, a powerful Mexican presence in the work of both, from the arum lilies (alcatraces) evoked by Diego to the motif in Frida of traditional Mexican dress. At the same time, one cannot deny a certain European influence in the sensibility of both: Frida’s father was German, and Diego spent formative years in Europe. However, the works in the exhibition from Diego’s (little-known) earlier phase bear the imprint of European genres, from Fauvism to cubism, and however Mexican the themes of his murals, one may divine a certain ideological influence of Soviet socialist realism. If originality is the quality most to be sought in an artist, preference is likely to incline towards the work of Frida, with its female self-interrogation, its integration of the natural world (in the repeated presence of animals such as dogs or monkeys), and the presence of a theme then as rarely evoked artistically as illness.

In the end, should we speak – as the exhibition’s title suggests – of an artistic ‘fusion’, or is it more a matter of a perpetual aesthetic conflict? If the balance inclines to Frida’s side, Diego’s major talent cannot be denied. It may be legitimate to take away from this exhibition a concept of the relation between man and woman which was more than prophetic for its time and anticipated the terrain of today’s and tomorrow’s interaction between the sexes – thus pointing towards a twenty-first century marked by the ever-growing and iconic fame of the extraordinary artist called Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo de Calderón – or, simply, Frida.