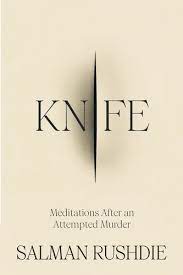

Salman Rushdie, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, London/New York: Vintage, 2024, 211 pp.

In this, the twenty-second of his long and distinguished line of literary works, Salman Rushdie tells the reader that ‘it was and is a book I’d much rather not have needed to write’ (173). This is hardly surprising as the triggering event, already signified in the book’s subtitle, is the near-fatal attempt on his life perpetrated on 12 August 2022 in a lecture theatre in Chautauqua in New York state, and its life-changing consequences. The painful nature of the material would have made it understandable had he not chosen to tell the world his story, but his final decision is vindicated by what proves, despite everything, to be a highly articulate and deeply felt piece of writing, liable to have a cathartic effect on both writer and reader, and a book to be shelved without reservation alongside its predecessors in its author’s oeuvre .

.

It is ironic that the attack should have occurred just as Rushdie was about to deliver a lecture on ‘the importance of keeping writers safe from harm’ (3). Had it succeeded, the attempted murder by a young Lebanese-American would have marked the delayed but definitive implementation, after 33 years, of Ayatollah Khomein’s fatwa of 1989 (the assailant, who admitted he had read all of two pages of The Satanic Verses, was an avowed admirer of the Iranian cleric). Thanks to hospitalisation, the best medical care and a dogged survival instinct, against all the odds Rushdie survived the multiple knife-wounds – losing his sight in his right eye and the full use of his left hand but with his mental faculties undimmed, in a process of treatment and recovery that some might wish to call miraculous. There is no question, however, of harping on near-death experiences or any religious or spiritual turn: Rushdie declares that he remains the non-religious person, indeed not to mince words atheist, that he always was: ‘My godlessness remains intact’ (186). The moving dedication prefixed to the book is humanist in tone (‘This book is dedicated to the men and women who saved my life’); and it is clear from his pages that if there is any discourse he believes in, it is that of love – love as personified by the constant presence across the book of his wife Eliza and her unconditional and unfaltering practical and emotional support right through her husband’s ordeal.

Salman Rushdie also reminds the world that he is first and foremost a novelist and a writer. He recalls how ‘for more than thirty years I have refused to be defined by the fatwa and insisted on being seen as the author of my books’ (132). Suddenly, he found himself back in the high-risk phase he had described in his earlier memoir Joseph Anton, reduced once again to ‘the author of The Satanic Verses’ (of ‘that novel’ – 23) despite his fifteen other works of fiction and the success (notably in his native India) of his latest novel, Victory City – but once he is well enough to visit the UK, back come the police protection and the ‘living at “undisclosed locations”’ (80), precautions he had deemed no longer necessary.

He reaffirms his long-standing role – in no way altered by the attack – in writerly circles as defender of free speech, as manifested in his presidency of PEN USA and his actions in support of beleaguered writers. Rushdie harks back to a lost innocence (when he began writing ‘that novel’, he says, ‘it never occurred to me that I wasn’t allowed to do it .. I had these stories I wanted to tell’ – 98). Years later but still on the same issues, Rushdie now in this book suggests a quite legitimate parallel between his own story and the murderous invasion of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo’s offices in 2015. He recalls that not all of his fellow writers were willing to defend the journalists killed in that attack, and notes that of those colleagues with whom he disagreed over Charlie, the ‘anti-Charlie clique’ as he calls them (191), to date none have so much as commented on the knife attack or expressed their sympathy. The PEN leadership, however, did offer their support, while Rushdie himself sums up free speech doctrine declaring that ‘in the rough-and-tumble world of politics and public life, no ideas can be ring-fenced and protected against criticism’ (183).

Rushdie’s writing in this book is concise and lucid, switching effortlessly between different registers, from the colloquial timbre of an imagined dialogue with his assailant, through technical legal discourse and pages of medical data which would not be out of place in The Lancet, to the compelling and economical narrative mode that best represents Rushdie as chronicler of our times. As usual, intertextuality is not lacking, from evocations of Shakespeare (Gloucester’s fate in King Lear – 95) and Kafka (the end of The Trial – 21) through to Nobel prize-winners José Saramago (Blindness – 197) and Bob Dylan, whose ‘Love Minus Zero’ is quoted twice (44, 69). The author also quotes the late nineteenth-century poet W.E. Henley, taking up from him three significant words, ‘bloody but unbowed’ (208), which could well describe the Salman Rushdie of these pages.

Meanwhile, with the assailant awaiting trial, the book ends with Salman and Eliza returning to Chautauqua a year after the attack, articulating the need to accept what happened, with their happiness ‘wounded’ and yet still ‘strong’ (209), and move on. This book is not for the squeamish, and some might find in it a plethora of gory detail. However, Rushdie’s narrative, taken as a whole, offers a breadth of scope that goes far beyond the triggering event, thanks to his reflections on the destiny and responsibility of the writer and, as he movingly reminds us across the book, the healing power of love.

Note added 22 April 2024: I reviewed ‘Victory City’ on this blog on 13 March 2023.

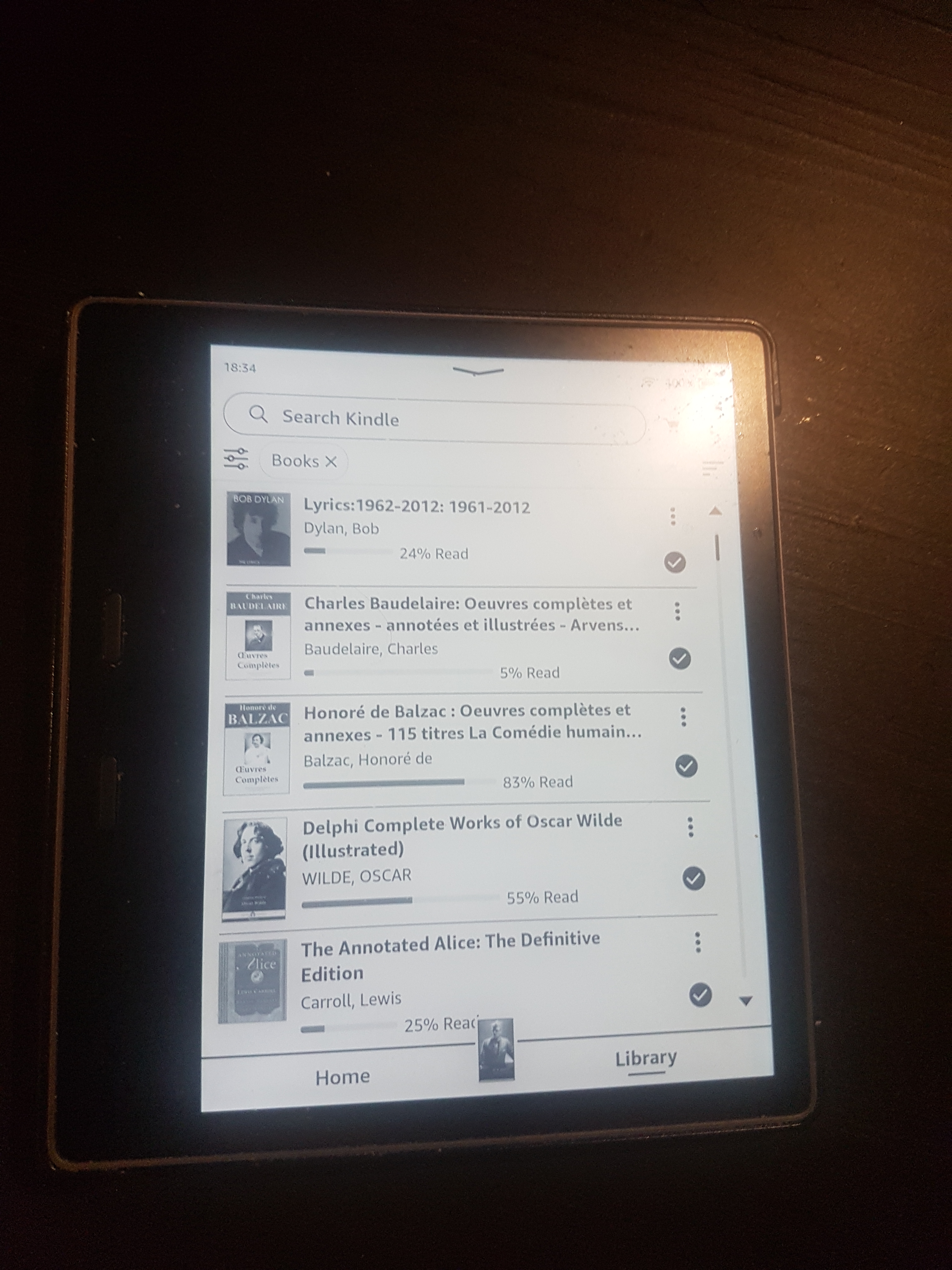

The small size of the device means it is fine for text but not so good for art books. Also the user has to remember to charge the battery, whereas a physical book is ‘always on’. In the academic world, Kindle editions may not be ideal for referencing, as many Kindle texts lack conventional page numbers.

The small size of the device means it is fine for text but not so good for art books. Also the user has to remember to charge the battery, whereas a physical book is ‘always on’. In the academic world, Kindle editions may not be ideal for referencing, as many Kindle texts lack conventional page numbers.